for Paul Guiragossian

• • •

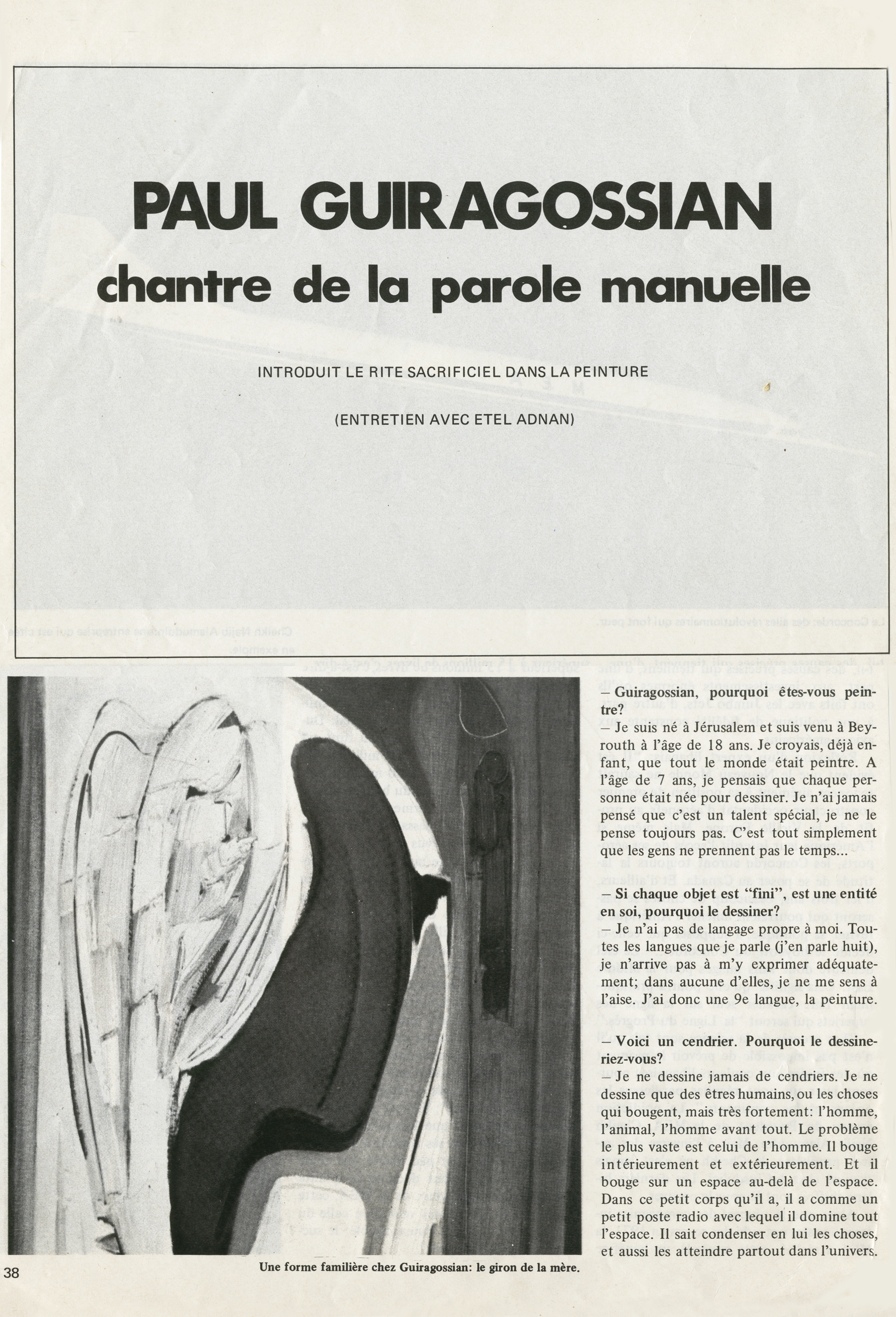

Etel Adnan’s interview with Paul Guiragossian, 1973. Photo courtesy of the Paul Guiragossian Foundation.

Before even reading the piece, my imagination began weaving a fiction about their meeting. I had separately encountered the works of these two contemporaries through my research, but this was the first time I visualized them in conversation. Until that moment I had not imagined their paths or trajectories crossing. Paul was born in Jerusalem in 1926 and forced into exile with his family in the years leading up to the creation of the state of Israel. Etel was born in Beirut in 1925 and spent a number of years in Europe and traveling North Africa while much of her adult life was spent on the West Coast of North America. Yet here on the pages of a French-language newspaper in 1973, they were speaking to each other.

In her interview, Adnan was playful and poignant. The clipping features three short, precariously straightforward questions, in which she is seemingly attempting to prod Guiragossian to elaborate on why he is an artist. Potentially part of a longer interview, the portion that has been documented by the foundation is a particularly poetic fragment.

For weeks, I wondered what the relationship between these two artists might have been like. Were they friends? Did they admire each other’s work? In what other ways did they interact beyond this four-decade-old article? I decided the only way to satiate my curiosity was to ask Etel in person. It turned out to be an ideal segue into what would turn into a delightful January afternoon of tea and conversations about love, politics, and Sufism.

Located a few quaint streets away from Saint Sulpice in Paris is the home and studio where Etel lives with her partner, artist, translator and publisher Simone Fattal. On the wall behind the couch where I sat, a small painting of Paul’s — featuring a line of clustered bodies, anonymous, elongated and rendered in varying tones of ochre on a sepia lime background — hangs beneath two of Etel’s own paintings from the 1980s of abstracted squares in green, white, and red. To see Etel’s atmospheric explorations of color, form, and landscape mingling with Paul’s introspective investigation of humanity felt like an eerily relevant backdrop given the impetus for my visit.

Etel did not remember the interview but she did remember Paul. For Simone, she recalled encountering the artist in the 1960s as a young woman and even posed for portraits, which she no longer has a record of. “I met him in ’72… he came often to visit Simone and I,” Etel said comfortably perched in her worn rose pink armchair. Then in her late forties, Etel had just recently returned to the city of her birth, leaving behind her fourteen-year tenure teaching philosophy in Northern California. Taking up a job as a columnist for a new Lebanese newspaper, Etel was given the freedom to write on politics, literature, and art. This interview with Paul was one of the many articles and interviews she published during her time as a journalist.

Etel said she regarded Paul’s body of work as “one long pilgrimage. Not [a] pilgrimage to a place, but an exile like pilgrimage,” remarking that his practice was in a sense an extension of his lived experience and those of the Armenians and Palestinians displaced by violence.

At one point in the conversation, Etel held the copy of the newspaper clipping in hand, squinting as she tried to make out the small print. Struggling to read it, she handed the paper to Simone, who uttered the questions and answers aloud in a careful, elegant and clear voice. Alternating between French and English, Simone’s jubilant recitation of the interview offered a new encounter and reading of these archived words.

“Why are you a painter? First question,” Simone relays to us. In Paul’s answer, he talks of being a young boy in Jerusalem and thinking that everyone was an artist. Art making, he insists, did not seem to be something special. It is something anyone could do if they took the time to nurture their creativity and curiosity.

Perhaps feeling he had not fully answered her question, Etel’s next question probes further — she asked him why objects are drawn if they already exist?

In response, Paul says that although he speaks eight languages, he cannot find comfort or express himself adequately through linguistic communication. Simone interprets his answer as “none [of these languages] can express what I can say, therefore I paint!” In hearing this, Etel enthusiastically responds, “How nice! This is a real reason!” Paul alludes to how art making for him is an inexplicable response to acknowledging and understanding existence.

Simone then translates the third question as Etel listens intently with an eager grin. In an almost assumptive tone, Etel had asked for Paul to draw an ashtray.

“And what did he say?” Etel laughs at the question. Although she must have been acutely aware that Paul’s practice focuses on human subjects, her invitation to draw this inanimate object is enough to provoke him to speak more intimately on why he chooses to paint figures. Simone laughs, reciting Paul’s answer: “I never draw any ashtrays! I only draw people, all things that move.” It is here that he reveals the core philosophical problematic of his practice: The most pertinent problem is that of the human being; one who has the ability to move internally and externally.

“He was a real thinker on every matter,” Etel says, conveying her deep reverence for a peer who passed away a quarter of a century ago.

This discovery of archival minutiae triggered both surprise and a slight anxiety in me as I considered all that might be missing to develop a nuanced understanding of modernism in the Arab region. In a time of growing sectarianism in the lead up to the Lebanese Civil War, the artifacts in the Paul Guiragossian Foundation archive point to a particularly momentous historical period of cultural production in Lebanon that brought both artists and writers together in deliberation and debate. Between the 1950s and 1970s, Beirut had become “the metropolis of Arab modernity;” a meeting point for political and cultural dissidents as well as a hub for the emerging first generation of artists who were refugees of Palestine after the formation of Israel in 1948. By the 1960s, Guiragossian had become one of Lebanon’s most celebrated artists.

Given the relative dearth of primary sources and documents chronicling the lives of modernist artists, it is difficult to anticipate all the possible correspondences and encounters between them. These could be testimonies of artists who have already passed and even more urgently, those who are still living. The presence and permanence of archives in the Arab region is also part of a wider critical conversation in scholarship. As art historian Nada Shabout notes, “One of the main problems with modernity in the Arab world is the lack of credibility, criticality and scrutiny in understanding, presenting, and evaluating its nature and objects.” What is more, what we accept as record can also be questionable, and thus the evolution of modernism and how it can be understood disrupts our ability to construct historical context.

At one point, Etel and I discuss the range of factors that contributes to the shortage of archives and the importance of addressing this going forward. “We are countries at war or invasions,’’ Etel says, “they say when Genghis Khan entered Baghdad they crossed the Tigris on foot because [of how] full of books it was. They burned the libraries. So we are constantly destroyed.”

As echoes of past and present destruction cause incalculable loss, there is a palpable sense of urgency to collect what is hidden, buried, and almost lost. More than building inventories and databases, the value of the archived record may not be in its dormant survival but, rather, what we do with it to bring it new meaning.

Before even reading the piece, my imagination began weaving a fiction about their meeting. I had separately encountered the works of these two contemporaries through my research, but this was the first time I visualized them in conversation. Until that moment I had not imagined their paths or trajectories crossing. Paul was born in Jerusalem in 1926 and forced into exile with his family in the years leading up to the creation of the state of Israel. Etel was born in Beirut in 1925 and spent a number of years in Europe and traveling North Africa while much of her adult life was spent on the West Coast of North America. Yet here on the pages of a French-language newspaper in 1973, they were speaking to each other.

In her interview, Adnan was playful and poignant. The clipping features three short, precariously straightforward questions, in which she is seemingly attempting to prod Guiragossian to elaborate on why he is an artist. Potentially part of a longer interview, the portion that has been documented by the foundation is a particularly poetic fragment.

For weeks, I wondered what the relationship between these two artists might have been like. Were they friends? Did they admire each other’s work? In what other ways did they interact beyond this four-decade-old article? I decided the only way to satiate my curiosity was to ask Etel in person. It turned out to be an ideal segue into what would turn into a delightful January afternoon of tea and conversations about love, politics, and Sufism.

Located a few quaint streets away from Saint Sulpice in Paris is the home and studio where Etel lives with her partner, artist, translator and publisher Simone Fattal. On the wall behind the couch where I sat, a small painting of Paul’s — featuring a line of clustered bodies, anonymous, elongated and rendered in varying tones of ochre on a sepia lime background — hangs beneath two of Etel’s own paintings from the 1980s of abstracted squares in green, white, and red. To see Etel’s atmospheric explorations of color, form, and landscape mingling with Paul’s introspective investigation of humanity felt like an eerily relevant backdrop given the impetus for my visit.

Etel did not remember the interview but she did remember Paul. For Simone, she recalled encountering the artist in the 1960s as a young woman and even posed for portraits, which she no longer has a record of. “I met him in ’72… he came often to visit Simone and I,” Etel said comfortably perched in her worn rose pink armchair. Then in her late forties, Etel had just recently returned to the city of her birth, leaving behind her fourteen-year tenure teaching philosophy in Northern California. Taking up a job as a columnist for a new Lebanese newspaper, Etel was given the freedom to write on politics, literature, and art. This interview with Paul was one of the many articles and interviews she published during her time as a journalist.

Etel said she regarded Paul’s body of work as “one long pilgrimage. Not [a] pilgrimage to a place, but an exile like pilgrimage,” remarking that his practice was in a sense an extension of his lived experience and those of the Armenians and Palestinians displaced by violence.

At one point in the conversation, Etel held the copy of the newspaper clipping in hand, squinting as she tried to make out the small print. Struggling to read it, she handed the paper to Simone, who uttered the questions and answers aloud in a careful, elegant and clear voice. Alternating between French and English, Simone’s jubilant recitation of the interview offered a new encounter and reading of these archived words.

“Why are you a painter? First question,” Simone relays to us. In Paul’s answer, he talks of being a young boy in Jerusalem and thinking that everyone was an artist. Art making, he insists, did not seem to be something special. It is something anyone could do if they took the time to nurture their creativity and curiosity.

Perhaps feeling he had not fully answered her question, Etel’s next question probes further — she asked him why objects are drawn if they already exist?

In response, Paul says that although he speaks eight languages, he cannot find comfort or express himself adequately through linguistic communication. Simone interprets his answer as “none [of these languages] can express what I can say, therefore I paint!” In hearing this, Etel enthusiastically responds, “How nice! This is a real reason!” Paul alludes to how art making for him is an inexplicable response to acknowledging and understanding existence.

Simone then translates the third question as Etel listens intently with an eager grin. In an almost assumptive tone, Etel had asked for Paul to draw an ashtray.

“And what did he say?” Etel laughs at the question. Although she must have been acutely aware that Paul’s practice focuses on human subjects, her invitation to draw this inanimate object is enough to provoke him to speak more intimately on why he chooses to paint figures. Simone laughs, reciting Paul’s answer: “I never draw any ashtrays! I only draw people, all things that move.” It is here that he reveals the core philosophical problematic of his practice: The most pertinent problem is that of the human being; one who has the ability to move internally and externally.

“He was a real thinker on every matter,” Etel says, conveying her deep reverence for a peer who passed away a quarter of a century ago.

This discovery of archival minutiae triggered both surprise and a slight anxiety in me as I considered all that might be missing to develop a nuanced understanding of modernism in the Arab region. In a time of growing sectarianism in the lead up to the Lebanese Civil War, the artifacts in the Paul Guiragossian Foundation archive point to a particularly momentous historical period of cultural production in Lebanon that brought both artists and writers together in deliberation and debate. Between the 1950s and 1970s, Beirut had become “the metropolis of Arab modernity;” a meeting point for political and cultural dissidents as well as a hub for the emerging first generation of artists who were refugees of Palestine after the formation of Israel in 1948. By the 1960s, Guiragossian had become one of Lebanon’s most celebrated artists.

Given the relative dearth of primary sources and documents chronicling the lives of modernist artists, it is difficult to anticipate all the possible correspondences and encounters between them. These could be testimonies of artists who have already passed and even more urgently, those who are still living. The presence and permanence of archives in the Arab region is also part of a wider critical conversation in scholarship. As art historian Nada Shabout notes, “One of the main problems with modernity in the Arab world is the lack of credibility, criticality and scrutiny in understanding, presenting, and evaluating its nature and objects.” What is more, what we accept as record can also be questionable, and thus the evolution of modernism and how it can be understood disrupts our ability to construct historical context.

At one point, Etel and I discuss the range of factors that contributes to the shortage of archives and the importance of addressing this going forward. “We are countries at war or invasions,’’ Etel says, “they say when Genghis Khan entered Baghdad they crossed the Tigris on foot because [of how] full of books it was. They burned the libraries. So we are constantly destroyed.”

As echoes of past and present destruction cause incalculable loss, there is a palpable sense of urgency to collect what is hidden, buried, and almost lost. More than building inventories and databases, the value of the archived record may not be in its dormant survival but, rather, what we do with it to bring it new meaning.

• • •

2018, Originally published in Jadaliyya and the exhibition book Paul Guiragossian: Testimonies of Existence